The Ten Little Fairies

VAINLY I try to recall from my recollections of

yesterday, still vividly remembered, and from those of the long past, grown tenderly dim in the mists of intervening time, from whom I learned the powerfully moral story I am here going to repeat to children great and small, to men and their companions: I cannot determine from whom it was I learned it.

Did I first read it in some old book laden with the dust of ages? Was it told to me by my mother, by my nurse, one evening when I would not go to sleep—or one night when, sleeping soundly, a fairy came and sang it to me in my slumber? I cannot tell. I cannot 172remember. I have forgotten all the details, of which there only remains with me the subtle perfume—too fine and evanescent for me to seize it in its passage through my mind. But I retain—perfectly retain—the moral, which is the daughter of all things healthy and strong.

The things which I am going to recount happened in a charming country—one of those bright lands which we see only in delightful dreams, where the men are all good and the women all as amiable as they are beautiful.

In that happy country there lived a great nobleman who, left a widower early in life, had an only daughter whom he loved more than anything in the whole world.

Rosebelle was seventeen years old—a pure marvel of grace and beauty; gay as a joyous heart, good as a happy one. For ten leagues round she was known to be the most beautiful and best. She was simple and gentle, and her exquisite ingenuousness caused her everywhere—in the mansion and the cottage—to be beloved.

Her father, fearful lest the least of the distresses of our poor existence should overtake her, watched over her with jealous care, so that no harm should come to her; while she passed her days in calmly thinking of the time before her, sure that it would not be other than delightful.

When she was eighteen, her father consented to her being betrothed to the son of a Prince—to Greatheart, a handsome youth, who had been carefully reared, and detested the false excitements and factitious pleasures of cities loving enthusiastically the fresh charms of

Nature—of the common other who claims us all, the Earth.

Rosebelle loved her fiancé, married, and adored him. With him she went to live in the admirable calm of the country, in the midst of great trees that gave back the plaint of winds, by a river with its ever-flowing song, winding under willowy banks, and overshadowed by tall poplars.

She lived in a very old, old castle, where the sires of her husband had been born—a great castle reached by roads hewn out of the solid rock; a great castle, with immense, cold halls, where echo answered echo mysteriously; where the night-owl drearily replied to the early thrush's song to the rising sun, and the other awakened birds singing and chirping on the borders of the deep woods, where the sun enters timidly—almost with the hesitation of a trespasser.

When the time for parting came, her father had said to her, through his tears:

"You are going from me—your happiness claims that I should let you go: go, therefore, but take all care of yourself for love of me, who have only you in the world to love."

To his son-in-law he said:

"Watch over her, I intrust her to you. Surround her with a thousand safeguards; screen her from the least chance of harm or pain. Remember that even in stooping to pluck a flower she may fall and wound herself, that in gathering a fruit she may tear her hand. See that all is done for her that can be done, keep her for me ever beautiful."

Absorbed in her love for her husband, Rosebelle realised the sweet dreams of her young girlhood. Then she dreamed—languorously—Heaven knows what! The delightful future which she had seen in the visions of the past was still present with her, however.

Her husband, tender and good, wished that she should do nothing but live and love. He had surrounded her with numerous servants, all ready to obey the least of her desires, the slightest of her fancies, to comprehend the most trivial of her wants. She had nothing to do but to let time glide slowly by her.

At length she wearied—languished mysteriously.

Her father, to whom she communicated this strange experience, was astounded. He reminded her of all the sources of happiness which ought to have existed in her case. He took her in his arms and said all he could think of in laudation of the husband who so greatly loved her; gave her innumerable reasons why her happiness ought to have been unparalleled; offered money—more money—wishful to give all the felicities in the world.

She wished for nothing of all that; it only tired, enervated her.

He besought her to be happy; she replied:

"I wish I could be so, for your sake and for that of my husband, whom I love so dearly."

And she struggled against the strange evil which so weighed upon her, against the deadly ennui that was sapping her young life. But the mysterious ill which tormented her soul grew and grew until it became overwhelming.

Greatheart speedily detected her distress, and sought

to discover its cause, but ineffectually; and from alarm he passed into despair.

"SHE VOWED FOR HIM A BOUNDLESS LOVE"

Now, when he returned from the plain, the fields, or the camp, when he embraced her he pressed against his

bosom a bosom cold and filled with sadness and tears—a bosom so cold that it might have been thought to contain a block of ice in place of a heart—and he redoubled his tenderness towards her. Seeing how much he was suffering on her account, she vowed for him a boundless love.

Courageous, energetic even, she tried to shake off the languor which possessed her, endeavouring to intoxicate her soul and drown her self-consciousness in the love of her adored husband; but all her efforts were made in vain; she became more and more oppressed with weariness, and the crowd of servants about her, all eager to realise her wishes, were utterly unable to mitigate her condition by anything they could do.

At last she fell into a state of the deepest melancholy. The rose-tints faded from her cheeks, her beauty paled like that of a languishing flower; the light in her eyes grew each day more dim. She was very ill.

The most learned doctors in the healing art were called to her, brought, regardless of cost, from the most distant countries, only to confess their complete inability; excusing themselves by affirming that there was no remedy for an indefinable ailment—an ailment impalpable, incomprehensible.

Then, one day, an old, white-haired shepherd, with a long, snowy beard, who had learned to understand men from having always lived alone with his sheep and thinking, thinking, while he led them to their pasture—an old philosopher—came to Greatheart, of whom he was one of the vassals, and said to him:

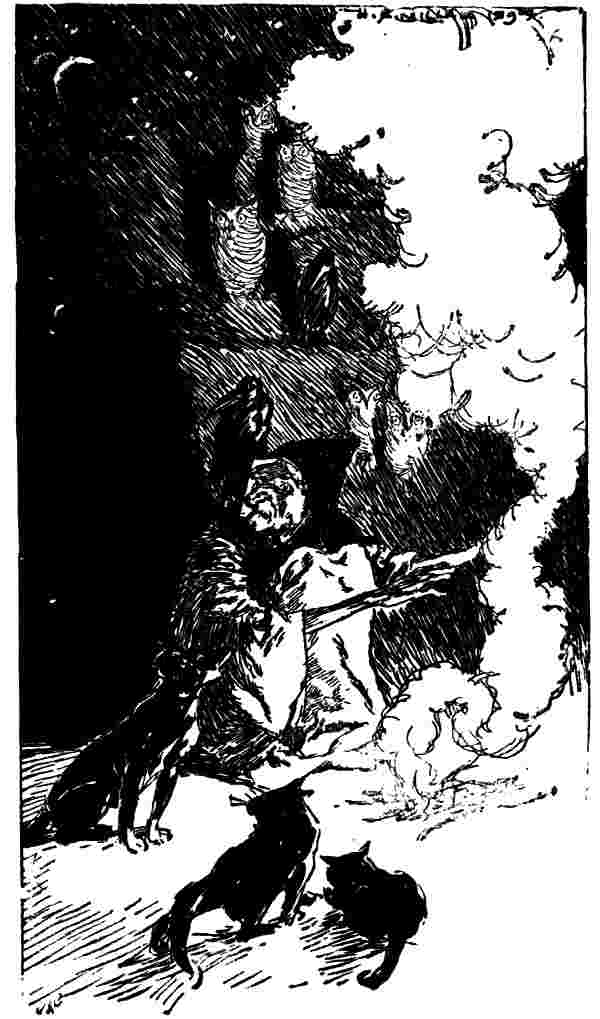

"I know where there lives, close by here, an old

grand-dame, with one foot in the grave, she is so old People call her a sorceress; but never mind that; she, and she alone, can cure our lady, our mistress, whom you love so well."

Knowing not what to do in his suffering, Greatheart believed what the old shepherd told him.

He took Rosebelle far away from the castle along the bank of the river, to a spot where the path ran between high rocks, leading to a deep and profoundly dark cavity, within which they found the old, old woman of whom the shepherd had spoken, crouching by the side of a scanty fire of pine-branches, warming herself in their fitful light, in the midst of owls and ravens, cats and rats with phosphorescent eyes, showing green in the obscurity when lit by the intermittent sparkle of the crackling branches on the hearth.

"Ho, there! sorceress!" cried the young Prince. "Cure my wife, and I will give you the half of all I possess!"

The very old woman looked for a long time at Rosebelle out of her little bright eyes, meeting those of the young Princess, and holding her as if by a spell. For awhile longer she remained silent, as if in contemplation; then, suddenly, she rose to her feet, raised her long arms towards the herbs suspended from the rocky roof of her dwelling-place, spread out her fleshless fingers and cried:

"I see! I see! I understand it all! Yes, my lord, I will cure your wife, your adored one; and presently in your arms, on your heart, shall sleep a heart beating with great joy for love of you!"

As they both sprang nearer to her, the better to

hear her wonderful words, the old woman retreated, saying:

"Yes, I will cure her; but to aid me in the task, I need the assistance of ten little fairies—ten friends who have ever been dear to me, ever faithful to me, and who, by an unfortunate chance, have not visited me to-day. To-morrow I shall be sure to have them with me, my tiny comrades; so come back to me to-morrow, my dear, when I will detain them until you arrive, and will take measures for enabling them to cure you."

The sun, next day, had hardly risen, hardly caressed the earth with its earliest beam, when Rosebelle re-entered the old sorceress's murky dwelling-place.

Over the still crackling fire of pine-branches she extended her white hands by direction of the old woman, who raised her arms and uttered some curious words, accompanied by some strange gestures.

Then, from a small cavity in the rocky wall she appeared to draw forth an invisible something, which she carefully conveyed to the shelter of her bare bosom. And when she had repeated these actions ten times, she cried:

"I have them!—I have them all!—all warm in my bosom—my faithful little fairies! Oh!—do not attempt to see them, or they will at once fly away. They desire to serve you—to cure you. Here they are!"

And laughing, dancing, and singing, the old, old woman tapped with the crooked thumb of her right hand the young Princess's ten extended fingers, while the quaint song she sang was gaily given back by the echo of the rocky vault above her. This was the song she sang,

holding the Princess's delicate fingers caressingly in her left hand:—

Then, still laughing heartily, she pressed Rosebelle's fingers tightly, and went on:

"They are all here, the wonderful little doctors! Guard them preciously; do not weary them; keep them by you and, to do all that, never give them a moment's rest so long as the sun shines in the sky. Keep on moving them—actively, rapidly—so long as you are awake. Now go, and come back to me when you are quite cured, returning me my trusty little fairies."

With her hands filled with this precious load, Rosebelle hurried home, and told Greatheart of her dear hope of a renewal of life.

Of an evening, thenceforth, for a long time, she would even refrain from eating, so as to leave herself more time to exercise her unresting fingers, in which the ten little fairies were tenderly housed. As soon as the sun had sunk beneath the earth she went to sleep, and as soon as daylight returned, she at once rose and began once again to move her fairy-laden fingers.

During many, many days she continued to move her

fingers in every way she could devise; but at length, growing tired of this useless play, she went back to her old friend the sorceress.

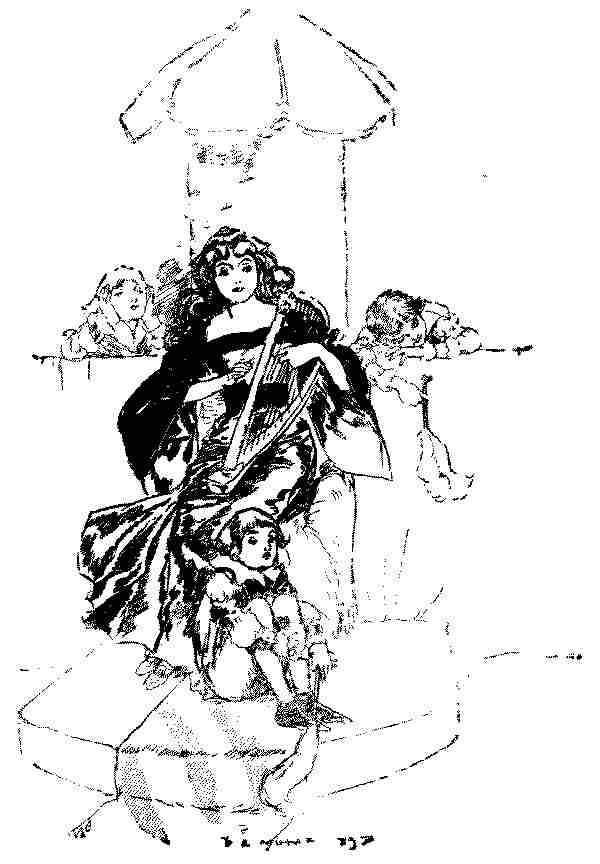

"ROSEBELLE DREW HER HARP FORM ITS CASE AND PLAYED ON IT"

"Nobody ever taught you to use your fingers usefully?" replied the old woman. "Go on moving them,

still moving them, but in some employment that interests you. Don't let my fairies go to sleep—that is all they desire in their imprisonment."

On returning home, Rosebelle drew her long-neglected harp from its case and played on it. Then, to occupy her fingers more usefully, she had needles brought to her and employed them in dainty sewing.

But, growing weary of the dull monotony of these labours, she sought more varied employment for her fingers—gathered flowers in the garden and arranged them in charming bouquets; plucked fruit from the trees in the orchard; attended to the sick and ailing; consoled the poor—exercising her fingers constantly by slipping gold pieces into their grateful hands.

One by one, she sent away her crowd of obsequious servants, who had now nothing left for them to do but to go to sleep at their posts.

She would not allow anybody to do anything for her which she could do for herself, but threw her whole soul and being into the things God intended to be done by them.

Every day, and all the while the sun shone in the sky, she found active employment for her beautiful fingers. And the roses came back to her cheeks and health to all her being, and songs and laughter to her lips; and she could, once again, give to her beloved one a heart filled with ineffable tenderness.

Perfectly cured, she went to the sorceress and gave her back her wonderful little fairy doctors.

"Ah, my child!" said the old dame, "they are very proud of having saved you. Give them to me, for I

have every day great need of them—can never have too much of them. Indeed, if I had enough of them to serve all the idlers in the world, I should want as many as there are stars in the heavens at night. But I will keep those I have for the service of those who are pining from ennui—and there are enough of them, goodness knows!"

Comments

Post a Comment