The Necklace of Tears

ONCE, many years ago, there lived in Ombrelande

a most beautiful Princess. Now, Ombrelande is a country which still exists, and in which many strange things still happen, although it is not to be found in any map of the world that I know of.

The Princess, at the time the story begins, was little more than a child, and while her growing beauty was everywhere spoken of, she was unfortunately still more noted for her selfish and disagreeable nature. She cared for nothing but her own amusement and pleasure, and gave no thought to the pain she sometimes inflicted on others in order to gratify her whims. It must be mentioned, however, as an excuse for her heartlessness, that,

being an only child, she had been spoilt from her babyhood, and always allowed to have her own way, while those who thwarted her were punished.

One day the Princess Olga, that was her name, escaped from her governess and attendants, and wandered into the wood which joined the gardens of the palace. It was her fancy to be alone; she would not even allow her faithful dachshund to bear her company.

The air was soft with the coming of spring; the sun was shining, the songs of the birds were full of gratitude and joy; the most lovely flowers, in all imaginable hues, turned the earth into a jewelled nest of verdure.

Olga threw herself down on a bank, bright with green moss and soft as a downy pillow. The warmth and her wanderings had already wearied her. She had neglected her morning studies, and left her singing-master waiting for her in despair in the music-room of the palace, that she might wander into the wood, and already the pleasure was gone.

She threw herself down on the bank and wished she was at home. There was one thing, however, of which she never tired, and that was her own beauty; so now, having nothing to do, and finding the world and the morning exceedingly tiresome and tame and dull, she unbound her long golden hair, and spread it all around her like a carpet over the moss and the flowers, that she might admire its softness and luxuriance, by way of a change.

She held up the yellow meshes in her hands and drew them through her fingers, laughing to see the golden lights that played among the silky waves in the sunlight; 1then she fell to admiring the small white hands which held the treasure, holding them up against the light to see their almost transparent delicacy, and the pretty rose-pink lines where the fingers met. Certainly she made a charming picture, there in the sunshine among the flowers: the picture of a lovely innocent child, if she had been less vain and self-conscious.

Presently she heard a slight rustle of boughs behind her, and looking round she saw that she was no longer alone. Not many paces away, gazing at her with admiring wonder, stood a youth in the dress of a beggar, and over his shoulder looked the face of a young girl, which Olga was forced to acknowledge as lovely as her own. Now, the forest was the private property of the King, and the presence of these poor-looking people was certainly an intrusion.

"What are you doing here?" said Olga haughtily. "Don't you know that you are trespassing? This wood belongs to the King, and is forbidden to tramps and beggars."

"We are no beggars, lady," said the youth. He spoke with great gentleness, but his voice was strong and sweet as a deep-toned bell. "To us no land is forbidden—and we own allegiance to no one."

"My father will have you put in prison," said Olga angrily. "What is your name?"

"My name is Kasih."

"And that girl behind you—she is hiding—why does she not come forward?"

"It is Kasukah—my sister," he said, looking round with a smile; "she is shy, and frightened, perhaps."

"What outlandish names! You must be gypsies," said Olga rudely, "and perhaps thieves."

"Indeed, lady, you are mistaken; on the contrary, it is in our power to bestow upon you many priceless gifts. But we have travelled far to find you, and are weary; only bid us welcome—let us go with you to the castle to rest—Kasukah——"

"How dare you speak so to me?" interrupted Olga, in a fury. "To the castle, indeed—what are you thinking of? There is a poor-house somewhere, I have heard the people say, maintained by my father's bounty out of the taxes, you can go there. Go at once—or——"

She raised the little silver-handled dog-whip which hung at her girdle. To do her justice, she was no coward. Kasukah had quite disappeared; the boy stood alone looking at Olga with sad, reproachful eyes. For a moment, she thought what a pity he was so poor and shabby; he had the face and bearing of a king. But she was too proud to change her tone.

"Or what?" he said.

"I will drive you away," she said defiantly. Still Kasih did not move, and the next moment she had struck him smartly across the cheek with the whip.

He made no effort at self-defence or retaliation, only it seemed to her that she herself felt the pain of the wound. For a few instants she saw his sorrowful face grown white and stern, and the red, glowing scar which her whip had caused; then, like Kasukah, he seemed to vanish, and disappeared among the trees, while where he had stood a sunbeam crossed the grass.

Olga felt rather scared. She had been certainly very

audacious, and it was odd that the boy should have shown no resentment. After all, she rather wished she had asked both him and his sister to stay, they might have proved amusing.

"GO AT ONCE"

However, it was too late now; she could not call them back; so she thought she would return to the

castle; she was beginning to feel hungry. So she went leisurely home, and, for

the remainder of the day, proved a little more tractable than usual. She did

not forget Kasih and his sister, and for a time wondered if they would ever seek

her again; but the months went by and she saw them no more.

Now, as Olga grew older, of course the question arose of finding for her

a desirable husband. And one suitor came and another, but none pleased her;

and, indeed, more than one highly eligible young Prince was frightened away by

her haughty manners and violent temper.

The truth was, that in secret she had not forgotten the face of Kasih, and she sometimes told herself that if she could find among her suitors one who was at all like him, and was also rich and powerful enough to give her all she desired in other ways, him she would choose. Kasih was certainly very handsome, in spite of his beggar's clothes; and, suitably dressed, he would have been quite adorable. Also, it would be delightful to find a husband with such a gentle, yielding disposition, who never thought of resenting anything she said or did.

And one day a suitor came to the palace who really made her heart beat a little faster than usual at first; he was so like the lost Kasih. But unfortunately he was only the younger son of a Royal Duke, and could offer her nothing better than a small, insignificant Principality and an income hardly sufficient to pay her dressmaker's bills. So it was no use thinking about him, and he was dismissed with the others. Olga's father began to think

his daughter would never find all she required in a husband, but would remain for ever in the ancestral castle: as every year she grew more disagreeable, the prospect did not afford him entire satisfaction.

At length, however, appeared a very powerful Prince, who peremptorily demanded her hand. He was a big, strong man, and carried on his wooing in such a masterful manner that even Olga was a little afraid of him. At the same time he loaded her with jewels and beautiful presents of all kinds, brought from his own country. He was said to possess fabulous wealth; and, partly because she feared him, and partly because of her pride and ambition, haughty Olga surrendered and promised to become his wife. Having once gained her consent, Hazil would brook no delay.

The date was immediately fixed, and the grandest possible preparations made for the wedding. No expense was spared, innumerable guests were invited, while those less favoured among the people came from far and near to see the bride's wedding clothes and to bring her presents. Indeed, the King of Ombrelande was forced to add a new suite of rooms to the castle to contain the wedding gifts and display them to the best advantage.

Such a sight as the bridal train had never been seen before, for it was spangled all over with diamonds so closely that Olga when she moved looked like a living jewel—and her veil was sprinkled with diamond dust, which sparkled like myriads of tiny stars.

The evening before the wedding day Olga sat alone in her chamber, thinking of the magnificence that awaited her, also a little of Hazil, the bridegroom. She had that day seen Hazil, in a passion, punish, with his own hands, a servant for disobedience, and the sight had displeased her. It had been an ugly and unpleasant exhibition, but worse than all, the sight of the poor man's wounds had recalled that livid mark across the fair cheek of Kasih which she herself had wrought. The boy's gentle face, which had become so stern when they parted, the laughing eyes of Kasukah, quite haunted her to-night. She thought she would like to make amends for her rudeness; if she knew where they were, she would ask brother and sister to her wedding. And just as she was so thinking, a soft tap sounded at the door, and before she could ask who was there (she thought it must surely be the Queen, her mother, come to bid her a last good-night, and felt rather displeased at the interruption) the door opened, and a stranger entered the room.

Olga saw a tall figure, draped from head to foot in a soft darkness that shrouded her like a cloud, obscuring even her face.

"Who are you?" said Olga, "and what do you want in my private apartments? Who dared admit you without my leave?"

"I asked admittance of no one, for none can refuse me or bar my way," answered the stranger, in a voice like the sighing of soft winds at night. "My name is Kasuhama—I am the foster-sister of Kasukah and Kasih, of whom you were just now thinking, and I come to bring you a wedding gift."

She withdrew her veil slightly as she spoke, and Olga

saw a pale, serene face, sorrowful in expression, and framed with snow-white hair, but yet bearing a likeness, that was like a memory, to Kasih and Kasukah.

"I COME TO BRING YOU A WEDDING GIFT"

"I wish," said Olga petulantly, "that Kasih had brought it to-morrow and been present at our feast. I would have seen that he was properly attired for the occasion.

Your sad face is hardly suitable for a wedding feast. Shall I ever see him again?"

"As to that, I cannot answer," said Kasuhama gravely; "but your wedding is no place either for him or Kasukah. As for me—I go everywhere. I am older in appearance than the others, you see, though, in reality, it is not so. But that is because they have immortal souls and I have none. The time will come when I must bid them farewell. We but journey together for a time."

The air of the room seemed to have become strangely chill and cold, and Olga shivered. "I am tired," she said, "and I wish to rest. Will you state your business and leave me?"

Experience had made her less abruptly rude than when she dismissed Kasih in the wood; also this cold, pale, soulless woman struck her with something like awe.

"Yes,—I will say farewell to you now. In the future you will know me better and perhaps learn not to fear me—but I will leave with you the present I came to bring."

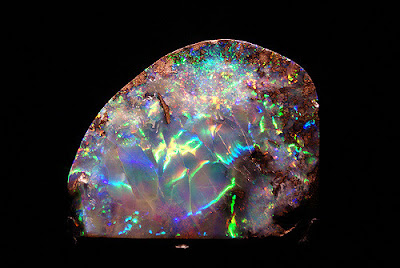

She held out a necklace of pearls more wonderful than even Olga had ever seen. They were large and round, lustrous and fair; but as Olga took them in her hands it seemed to her that, in their mysterious depths, each jewel held imprisoned a living soul.

"Wear them," said Kasuhama; "by them you will remember me."

Almost involuntarily Olga raised her hands and fastened the necklace around her slender throat. The clasps just met, and the pearls glistened like dewdrops on her bosom—or were they tears?

But in the centre of the necklace was a vacant space.

"There is one lost!" she said.

"Not lost, but missing," answered Kasuhama softly. "One day the place will be filled, and the necklace will be complete." And with these words she waved her hand to Olga, and, drawing her dusky veil around her, quitted the room as quietly as she had entered.

The ceremonies of the following day passed off without let or hindrance, and Olga, dazzled by her grandeur, would have thought little of her visitor of the previous night—would indeed have believed the incident a dream, a trick of the imagination—but for the necklace. It still encircled her throat, for her utmost efforts proved unavailing to unfasten the clasps, and every one stared and marvelled at the wonderful pearls which seemed endowed with a curious fascination.

Only Prince Hazil was displeased; for he could not bear his bride to wear jewels not his gift, and that outshone by their lustre any he could produce; also, he was jealous of the unknown giver. When the wedding was over, and they were travelling away to the distant castle where the first weeks of Olga's new life were to be spent, he tried to take the jewels from their resting-place. Olga smiled, for she knew that even his great strength would be unavailing, and so it proved; and although on reaching their destination Hazil sent for all the Court jewellers, neither then nor at any other time could the most experienced among them loosen Kasuhama's magic gift from its place.

The months rolled by, and Olga reigned a Queen in her husband's country, but her life was a sad one. Hazil was

often cruel, and it seemed as though he were bent upon heaping upon her all the contumely and harshness she had shown to others. Still her proud spirit refused to yield. She met him with defiance in secret, and openly bore herself with so much cold haughtiness that no one dared to hint at her trouble, much less to offer her any sympathy.

But when alone in her chamber she saw again the faces of Kasih and Kasukah; but more often that of Kasuhama. For the necklace was still there to remind her; the pearls still shone with mysterious, undimmed lustre; indeed, they seemed to grow more numerous, and to be woven into more delicate and intricate designs, as time went on. Still, however, the place for the central jewel remained unfilled. Often Olga herself tried with passionate, almost agonising, effort to break their fatal chain, for every day their weight grew heavier, until she seemed to bear fetters of iron about her fair throat, and when the pearls touched her they burned as though the iron were molten.

Still, in public, they were universally admired, and gratified vanity enabled her to bear the pain and inconvenience without open complaint.

But one day was placed in her arms another treasure—a beautiful living child, and she was so fair that they called her Pearl, but the Queen hated the name. The child, however, found a soft place in Hazil's rough nature; indeed, he idolised her; but Olga rarely saw her little daughter, and left her altogether to the care of the nurses and attendants.

"HE TRIED TO TAKE THE JEWELS FROM THEIR RESTING-PLACE"

So little Pearl grew very fragile, and had a wistful look in her blue eyes, as though waiting for something

that never came; for in her grand nurseries and among all her beautiful playthings she found no mother-love to perfect and nourish her life.

And all this time Olga had seen no more of Kasih or Kasukah; had, indeed, almost forgotten what their faces were like. But one night, at the close of a grand entertainment, she was summoned in haste to the nursery. The Court physician came to tell her that little Pearl was ill.

Olga was very weary. Never had the necklace seemed so heavy a burden as that night, or the Court functions so endless. She rose, however, and followed the physician at once. Hazil, the King, was far away, visiting a distant part of his great territory; he would be terribly angry if anything went wrong with little Pearl during his absence.

She reached the room where the child lay on her lace-covered pillows, very white and small, but with a happy smile on her tiny face, a happy light in her blue eyes, which looked satisfied at last. But Olga knew that the smile was not for her, that the child did not recognise her, would never know her any more.

Some one else stood beside the couch: a stranger with bent head and loving, out-stretched arms, and little Pearl prattled in baby language of playthings and flowers and sunlight and green fields. Olga drew near and watched, helpless and terrified, with a strange despair at her heart. And soon the little voice grew weaker—but the happy smile deepened as the blue eyes closed.

And there was a great silence in the nursery. The stranger lifted the little form in his arms, and as he raised his head Olga saw his face, and she knew that it was Kasih come at last, for across his cheek still glowed the red line of the wound which her hand had dealt many years before. His eyes met hers with the same stern sadness of reproach as when they had parted—then she remembered no more.

When the Queen recovered from her swoon they told her that her little daughter was dead; but she knew that Kasih had taken her. She said no word and showed few signs of grief, but remained outwardly proud and cold, though her heart was wrung with a pain and fear she could not understand. She was full of wrath against Kasih, who, she thought, had taken this way of avenging the old insult she had offered him. Yet the sorrowful look in his eyes haunted her.

The pearls about her neck pressed upon her with a heavier weight, and in her sleep she saw them as in a vision, and in their depths she discerned strange pictures: faces she had known years ago and long since forgotten, the faces of those whom her pride and harshness had caused to suffer, who had appealed to her for love and pity and were denied.

And then in her dream she understood that the pearls were in truth the tears of those she had made sorrowful, kept and guarded by Kasih in his treasure-house, but given to her by Kasuhama to be her punishment.

Before many days had passed, the King Hazil returned, and when he learned that his little daughter was dead, he summoned the Queen to his presence. Olga went haughtily, for she dared not altogether disobey. Then Hazil loaded her with reproaches, and in his anger he told her many, many hard things, and the words sank deep into her heart. It seemed, presently, that she could bear no more, and hardly knowing what she did, she cast herself at his feet and prayed for mercy.

She asked him to remember that the child had been hers also—that she had loved it. But Hazil, in his bitterness, laughed in her face and told her she was a monster, that it was for lack of her love that the child had died, that she had never loved anything—not even

herself. He turned away to nurse his own grief, and Olga dragged herself up and went away to the silent room, and knelt by the little couch where she had seen Kasih take away her child.

And there at length the blessed tears fell, for she was humbled at last, and sorry, and quite desolate and alone. And it seemed to her that through her tears she once more saw Kasih, and that he held towards her the little Pearl, more beautiful than ever, and the child put its arms about her neck, and she was comforted.

Well, from that day the life of the Queen was changed. When next she looked at the pearl necklace she found that a jewel, more beautiful than any of the others, had been added to it; and she knew that the tear of her humiliation had filled the vacant place.

And henceforth she often saw the face of Kasih: near the bed of the dying, beside all who needed consolation, kindness, and love, there she met him constantly. Near him sometimes she caught a glimpse of bright Kasukah, but for a while, more often of Kasuhama.

The face of the white-haired sister, however, had grown very gentle and kind, and she whispered of a time when Kasukah should take her place for ever—for Love and Joy are eternal, but Sorrow has an end. And with every act of unselfish kindness and love that the Queen Olga performed the weight and burden of the necklace grew less, until the day that it fell from her of its own accord, and she was able to give it back to Kasuhama. And Hazil, the King, seeing how greatly Olga was changed, in time grew gentle towards her, and loved her; for Kasuhama softened his heart.

Comments

Post a Comment